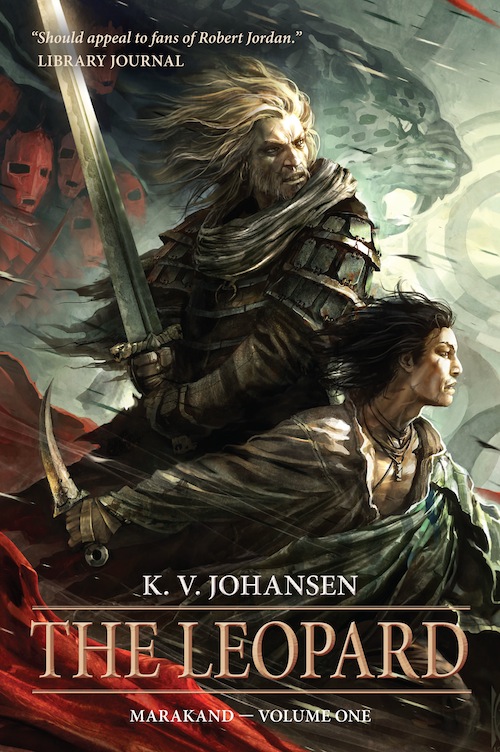

Check out The Leopard, volume one in K. V. Johansen’s Marakand series, available June 10th from Pyr!

Ahjvar, the assassin known as the Leopard, wants only to die, to end the curse that binds him to a life of horror. Although he has no reason to trust the goddess Catairanach or her messenger Deyandara, fugitive heir to a murdered tribal queen, desperation leads him to accept her bargain: if he kills the mad prophet known as the Voice of Marakand, Catairanach will free him of his curse.

Accompanying him on his mission is the one person he has let close to him in a lifetime of death, a runaway slave named Ghu. Ahj knows Ghu is far from the half-wit others think him, but in Marakand, the great city where the caravan roads of east and west meet, both will need to face the deepest secrets of their souls, if either is to survive the undying enemies who hunt them and find a way through the darkness that damns the Leopard.

Prologue?

In the days of the first kings in the north, there were seven wizards…

Mountains rose into a frost-cold sky, but she lay in a hollow of ash and cinder and broken stone. Fire ringed her, lighting the night. She could not move. The dead did not. Her body had faded and failed; well, she had never felt it was hers, anyway. Even the woman she had been before… before she was what she had become, when she was only one, weak and mortal, solitary, that woman had not felt she owned her body. It had never been more than an awkward shroud of flesh, a thing wrapping her, a thing that betrayed her, a thing he owned. Since she was a child, she had only lived in it, a prison of hip and breast and smooth brown skin. She had longed to leave it behind, and never dared. He would be hurt if she left him behind, and she mustn’t hurt him, ever. He had saved her life when they were children, or he a youth on the edge of manhood and she still a child. The war-canoes came out of the south and the king’s palace burned, flames rising from its wide verandas, and the great village burned, all the palm-thatched houses, and the fishermen’s huts on the white beach.

Who had they been, she and her brother? Noble or servant, tiller or fisher? She did not remember. She remembered the raiders, the folk of the next island but one southwards, the strange accents, the stone axes. She remembered a man with red feathers in his hair and a gold ring around his neck. She—no, she did not remember that. She would not. She remembered her brother, looking down on her, and a spear standing out from the red-feather man’s back. Her brother had not said anything, only flung his own sealskin cape over her nakedness and walked away into the night, but she had followed. They had salvaged a canoe and left, going island to island, sometimes staying, taking service here or there, that chieftain, this queen, that king, but travelling, travelling… no-one liked her brother to stay long. They did not like his eyes. He doesn’t blink enough, a woman had told her once, a wizard who wanted to take her as an apprentice. She didn’t even let her brother know the offer had been made. She had known what his answer would be. Her brother warned her against the danger of allowing strangers to falsely try to win her love.

Wizards, royal wizards, they had been, before their king and his queens were slain and his palace burned. Her brother said so, and whether it was truth or lie she did not know. It might have been true. It became that. He learned from every master he found, and took what learning was not given willingly. They had the strength, the two of them together. They took the knowledge to make his strength dreadful. He could have made himself a king, but that wasn’t what he wanted. In time they came all the way up the islands to Nabban. Such a vast land, not an island, and beyond it, land and land and no ocean, lands even without water, lands where water stood half the year turned by cold to stone, and still he pulled her on with him, never sated. He would learn more, be more. Always. And she followed. Of course she did. He was all she could call hers.

But now she was dead, or near enough. Flesh had long rotted, and it was over. Now she was her own. She could sleep through the centuries, a conjoined soul bound still in the remnant of a human body, a lace of bones buried in ash and cinder, protected by a fire that never died. The Old Great Gods and the wizards allied with them had thought it a prison as well as a grave when they left her here, bound in spells that they believed the seven devils themselves could not break. And that meant even he, who was the strongest of them all, could not come at her. She was… her own, as the long years did pass, and she knew peace.

But the bonds of the Old Great Gods failed. Not all at once. Slowly, fretted away by cautious and patient work. First one, then another, ravelled them to nothing and stretched again into renewed life, crawled from the grave, walked the world.

Not she. She did not want the world. She wanted sleep; she wanted forgetting. The wall of flame, which would burn so long as the strange gases roiled in the earth and found vents to the air, was no prison but a safe castle, all her own. Her undying fire would hold her, safe and warm, forever, and the spells that bound her in what could pass for death were spells of sleep and safety, like a lullaby woven over a baby. The little soul of the earth that guarded her, a creature of fire, a demon whom she knew only as a flicker lizard-like over her mind, was all the companion she needed. It never spoke.

Her brother called her.

She did not answer. She would not wake. He could not reach her here, safe behind her wall, behind flame born of earth and lightning, of deep and secret wells. Like a little child, she curled her soul-self up small and still, trying to be invisible, intangible. She was dead, but not dead enough. He had found her.

One day, he was there amid the broken mountains, standing on the edge of her flame.

Come, he said, and when she pretended she was not there, he dragged the chains of the Old Great Gods from her interwoven double soul, from her bones, and forced flesh to those bones again, shaping her, not as she had been, not the woman she had grown into, but the girl of the islands, the little sister.

Open your eyes, he ordered. See me. Come with me. We are betrayed.

The little demon of the fire flung its flames about him, trying to keep her, to defend her as no one ever had—her gaoler, warder, companion of centuries. Her brother snarled and burned into flame himself, golden, brilliant, furious. He tore down the walls, found the demon’s heart, the heart of the flame, and crushed it, reached for her—

Her flames. Her guardian. Her castle of peace. Her abhorred body woke and stirred and she sang the names of cold at him, of ice, of the deep black of the sea. No more. Never again. Never, never, never, never, never…

She had never raised a hand against him, never a word in all the long years. He screamed, drowning, freezing; screamed more in fury than in pain, that she, she of all people, she who belonged to him and him alone, should dare.

And he lashed out. He sang the names of fire, the fire of the forge and the burning mountain, the fire that lay in the secret hearts of stars. Her walls of flame roared hot and white, closed in, a fist clenched upon her, upon new flesh and old bone, upon ancient soul and baffled child. If not mine, he screamed, then whose are you? Then whose, traitor?

His fire devoured her. She screamed and could not scream, flesh consumed, bone flaking to ash, and she burned, burned. Her souls, soul, two spun into one, fled down and down, following the vents of the flame that had not, in the end, been enough to keep her safe. Down to the deep ways, the hidden, secret ways of the earth, down the chain of the mountains, far beneath their roots. She fled and pain followed, but then between the layers of the stone there was water. It was cold, and kind. It eased the pain of her twofold soul, which had not even bone left to feel. Old water, patient water, it waited for the day it could course free again. Could she become water? Without form belonging to the world to anchor her in the world, she would perish. Suddenly she was afraid. True death, true finality, true oblivion held out the arms she had thought she longed to have enfold her, and she fled them. She tried to shape herself to water and could not, but all unexpected the water opened to hold her, to hide her; in pity and mercy it offered sanctuary, embracing her and the water said, Who are you? What are you? Don’t fear. Rest here, be safe.

She saw how she could be safe. She could hide within water. Her brother would not see her; he would not know her; he thought he had killed her. So long as he thought her destroyed, she was safe. So long as he did not come to this place or send eyes to this place, she was safe. The water, the old, patient, mild water, all its wild and its wilderness for-gotten, held her as a mother holds her child, offering love and comfort.

But then she realized the truth. She was a small, weak, lost thing, an ember, a guttering light with the great cold darkness reaching to her. So was the water. It was only a reflection of broken light, a whispering echo that had not yet ceased to sound. It was weak; this goddess was weak. This deity of the water could not offer shelter or mercy or safety. This was a trap. Her brother would hunt her. He would come, he would…

But not if he did not see her. She would make certain he did not see her. He would see water. She could wear water. She could be water, within the water’s shell, within the shape of water, within, within, within, deeper within, burning, where the heart of water lay…

And in the days of the first kings in the north, there were seven devils…

The Voice of the Lady of Marakand, the goddess of the deep well, was serving pottage in the public dining hall when the ladle dropped unheeded from her hands. The old man whose bowl she had been filling backed away, nervous.

“Revered?” he asked. He knew who she was, of course. Though the priests and priestesses of the Lady of the Deep well served, in humility, the poor of the city, feeding any who came to their hall for the evening meal, the white veil over her black hair proclaimed her not merely any priestess, but the Lady’s chosen, the one who spoke face to face with the shy, underground goddess and carried her words from the well. He knew also, that she—or the goddess who sometimes spoke through her—was occasionally gifted with prophecy.

“Lady?” the Voice whispered. Her eyes fixed on the old man, wide and black. He backed further away, looking around, and the queue shuffling along the serving table, taking bread and pottage and sweet well-water from the hands of saffron-robed priests and priestesses, bunched in confusion behind him. “Where—? Lady? Lady!”

“Revered one,” he whispered hoarsely to a young priest hurrying up, a sweating pitcher of water in each hand. “Revered one, I think… I think the Voice has need of you.”

“Lilace?” asked another priestess. “What is it? Are you ill?”

The Voice flung up her arms before her face as if to shield it, shrieking, and then turned her hands, clawing at her own cheeks. “No!” she cried. “No! No! No! Out! Get out! It hurts! It hurts! It burns!”

“Voice!” cried the young priest, and he dropped the pitchers, spilling the sacred water, to lunge across the table for her wrists.

“Death! Not like this! No!”

Priests and priestesses clustered around.

“Lilace, hush! Not here! And who is dead?”

“Stand away from her, you people.”

“Give us room here.”

“Go to the benches, sit down, out of the way.”

But the line of charity-seekers did not disperse, of course. They pressed in about the clerics, those at the front staring and silent, those at the back clamouring to know what was happening.

“The Voice prophesies.”

“What does she say?”

“A fit, she’s having a fit.”

“My brother has fits. You should lay her down on her side…”

“Away, away!” The Right Hand of the Lady pushed through, Revered Ashir, a youngish man for his high office, but balding, easy to take for older. He elbowed the other priest aside and leaned over the table to shake the Voice, which did no good, and then to slap her, which drew shocked murmurs and hissings of breath from those around, but likewise achieved nothing useful. The priestess who had been serving the bread wrestled Revered Lilace from behind, trying to force her arms down, but she could not overcome the Voice’s frenzied strength. Lilace’s nails grew red with her own blood; she turned on the priestess who held her, raking that woman’s face. The Right Hand cursed irreligiously and scrambled over the table, but the Voice, breaking away from his snatching hands, fled, the white veil of her office floating behind her.

“Lilace—Revered Voice!” Ashir gave chase, leaving others to look to the injured woman. “Lilace, what did you see?”

The entrance to the well was covered by a squat, square, domed building of many pillars, the double doors in the entry porch carved and painted with flowering trees. The Voice reached it before the Right Hand and fled within, down the stairs, not stopping to light a torch at the carefully-tended lamp, down into cool, moist air, where the walls were carved from the layers of living rock and the stone sweated. The stairs ended at a dark, still reservoir.

“Lady!” Ashir heard her wail as her feet splashed into the water. “Lady, come to me!”

The earth heaved. The earthquake tossed Marakand like a householder shaking dirt off a rug.

It was three days before the survivors of the Lady’s temple thought to dig out the entrance to the deep well, to recover their Right Hand and their Voice. Revered Ashir was alive, though weak with hunger. The dome of the well-house had stood firm, only the porch had fallen in the earthquake, blocking the door.

The Voice, however, rocked and muttered, playing with her fingers like a baby, as she had, Ashir said, ever since he dragged her out of the heaving surface of the sacred pool onto the stairs. Her eyes focused on nothing, blank as stones, but she spoke as they carried her to the hospice, which, by chance or the Lady’s grace, was the least damaged of the temple buildings other than the well-house.

“Let all the wizards of the temple go to the Lady in her well. She calls them. She calls, she calls, she calls, let them go now, they must go now, make haste, haste, haste, haste, she calls… Let the wizards of the library be summoned to her, let the wizards of the city be brought before her, she has need of them, she will have them, she must—they must—No, no, no, no…”

In the end they drugged Revered Lilace into sleep to silence her, and prayed for her. The several priests and priestesses who were wizards, the one weakly wizard-talented of the temple dancers, and a son of the Arrac-Nourril, who, being devout, had come to help dig out the temple’s survivors rather than those in his own ward, answered the summons at once. All went down the steps of the deep well to face their goddess.

None came back. Not that day. Nor the next, as Revered Rahel sent messengers out to the city and the undamaged caravanserai suburb north and west of the city walls with the summons. Hearing that the Voice summoned wizards in the Lady’s name, they came, scholars from the library, both native-born and foreign visitors, scruffy outlander rovers from the caravans, wizards in the service of the Families or sooth-sayers from the nearby villages of the hillfolk of the Malagru and the silver-mines of the Pillars of the Sky. Some thought it meant a paid commission, involvement in rebuilding and restoration; some for pity and mercy, wanting to use what skills they had to bring aid to the stricken city.

None came back from the deep well.

And after that, two of the three gods of Marakand fell silent, and there was only the Lady of the Deep well, and the Voice of the Lady to speak her will.

The Leopard © K.V. Johansen, 2014